When Willie Davis passed away on April 15, Jerry Kramer lost one of his best friends. They had a close relationship which spanned close to 60 years. A number of the great memories that the two of them had will be shared in this story.

Thanks to the heartwarming and also heartbreaking movie Brian’s Song, people became aware that Gale Sayers and Brian Piccolo were the first black and white NFL players to room together. But what a lot of people don’t realize is that Willie and Jerry were the second black and white roommates in the NFL. That happened in 1968.

That strong friendship happened due to just a brief comment that Davis made to Kramer late in the 1962 season.

“We were in Los Angeles at the practice facility,” Kramer said. “We were getting to play the Rams. Back then, we always played the last two games of the season in Los Angeles and San Francisco. We had finished practice and I was getting ready to take a shower.

“So I had a towel around my waist and I was heading to the shower. Anyway, I stopped to chat with one of the guys and Willie was in that area. So I’m talking to the guy and Willie came by and said, ‘J, you had a hell of a season and I think you are going to make the All-Pro team.’ I thanked him, as it was a nice compliment. It was a big moment for me, because I had been named All-Pro once before, but you were never certain you might make it a second time.

“Willie then walked on and headed into the shower. After I finished my conversation, I went into the shower. I kept thinking to myself that was a nice thing for Willie to say to me. But I thought beyond that and I remembered that Willie had a hell of a year as well. He should have been All-Pro too. So I told him that. Willie had never made All-Pro up to that point and he was very pleased to have me say that to him. He thanked me for the compliment.

“Both of our comments were genuine too. When didn’t judge each other because of our color. We judged each other based on our contribution to the team. It was just a case of two guys playing on the same team who were making a difference and recognizing that fact.”

When the 1962 season was over, not only did the Packers win their second straight NFL title in a game in which Kramer received a game ball because of his play, but also Kramer and Davis were indeed named Associated Press first-team All-Pro along with eight of their teammates on the Packers.

In 1963, the Packers first-round draft choice was Dave Robinson out of Penn State. In his first two years in the NFL, Robinson saw spot duty at right outside linebacker and started seven games there. But in 1965, Robinson was moved over to left outside linebacker, where he would play behind Davis at left end.

Robinson commented about the left side of the Green Bay defense then.

“I want to tell you something. I felt that we had the strongest left side defense in the history of the NFL,” Robinson said. “Our leader was Willie Davis! Willie was the defensive end and I was behind him at linebacker. Behind me was Herb Adderley at cornerback. Sometimes middle linebacker Ray Nitschke would shade to the left, as did safety Willie Wood.

“That means that when we lined up in that formation, we had five players on the left side of the defense who were future Hall of Famers. Willie Wood was the one who kept the entire defense together, but it was Willie Davis who kept our left side strong. Nobody could run the same play on us twice successfully. ”

Robinson remembered a time when that happened against the Cleveland Browns.

“I remember very distinctly that we were playing Cleveland,” Robinson said. “Willie always had big games against Cleveland because they were the ones who traded him. On this one play, the tight end tried to hook me, while the tackled pulled to the outside. Willie went with the pulling tackle naturally and what happened was the Browns then brought the off guard behind him who blocked Willie in the back. It wasn’t a clip. You could do that then on a play tackle-to-tackle.

“So Willie got knocked down and Leroy Kelly gained like seven or eight yards. Willie was mad and he yelled to the Browns, “You can take that play and throw it in the shit can because it won’t work no more.’ So in the huddle, Willie tells me if they run that play again, that I have to take the tackle and the tight end, because he was going to close on that guard. I said okay. I’m thinking to myself, how can I handle two men? But you didn’t argue with the “Doctor” when he told you something.

“Sure enough, three or four plays later, they called the same play again. So Willie took one step like he was going to chase the tackle and then stopped and waited for the guard. He put the guard on the ground with a forearm and then picked up Leroy Kelly and just slammed him to the ground. And Willie says to Leroy while he was stuttering a bit, ‘I…I…I told you not to run that play no more!’

In the 1965 NFL title game at Lambeau Field against those same Browns…Davis, Robinson, Nitschke and company held the great Jim Brown to just 50 yards rushing in a game which turned out be his last ever in the NFL.

Meanwhile, the running attack of Paul Hornung and Jim Taylor combined for 201 yards and a score behind the blocking of Kramer, Fuzzy Thurston and company, as the Packers won 23-12.

Another play which involved Davis and Robinson occurred when the Packers were playing the Baltimore Colts at Memorial Stadium in Baltimore late in the 1966 season.

A win would clinch the Western Conference title for the Packers, while a win by the Colts would give them a slight chance to still win the title. Quarterback Bart Starr started the game at quarterback for the Packers, but after an injury, was replaced by the best backup quarterback in the NFL at that time, Zeke Bratkowski.

Bratkowski led the Packers to a touchdown drive in the 4th quarter which gave the Packers a 14-10 lead. But quarterback Johnny Unitas had the Colts driving late in the game and a touchdown would win the game for Baltimore.

Robinson remembered that moment well.

“Yes, Johnny had them on the move,” Robinson said. “I saw Unitas running with the ball and he looked at me and I looked at him and he tried to give a little rooster move, the old head and shoulders fake. When he did that, he held the ball away from his body a bit and I saw big Willie’s hand come out and hit right on the ball and it came out and hit the ground.

“It popped up and I picked it up. I knew all I had to do is hold on to the ball and we would win the game. I ran about five yards or so and a bunch of Colts were trying to pry the ball out of my hands before I finally went down.”

The Packers won their second straight NFL title in 1966, plus won Super Bowl I, when Davis had two sacks in the game, as Green Bay defeated the Kansas City Chiefs 35-10.

In 1967, which was Vince Lombardi’s last year as head coach of the Packers, the Packers won their third straight NFL title by beating the Dallas Cowboys in the “Ice Bowl” game, plus also won their second straight Super Bowl, as they defeated the Oakland Raiders 33-14 in Super Bowl II. Davis had three sacks in that game, which gave him five sacks in two Super Bowl games.

That storybook 1967 season was chronicled by Jerry in the classic book Instant Replay, which was edited by the late, great Dick Schaap.

Kramer, Davis and Robinson had put together quite a legacy for themselves up to that point going into the 1968 season.

Kramer had been named AP first-team All-Pro five times and he been on three Pro Bowl teams. Davis had been named AP first-team All-Pro five times himself, plus had been on five Pro Bowl teams. Robinson, who got his first chance to start full-time in 1965, had become part of the best group of linebackers in the NFL, along with Nitschke and Lee Roy Caffey. Robinson was named AP first-team All-Pro in 1967 and had been on the Pro Bowl teams in both 1966 and 1967.

Heading into training camp in 1968, Kramer knew he would be without his old roommate, Don Chandler, as No. 34 had retired.

“Willie and I knew that we were both in the latter portion of our careers at that point, Kramer said. “So we would talk about what happens after retirement. I asked Willie what his plans were, as he had been doing a lot of studying, because he had gotten his MBA at the University of Chicago. So we would talk about the radio business, communications and restaurant franchises.

“I mentioned to him that there was a new steak house in town and that it was a franchise and it looked pretty hot. I said that we ought to go look at it. Willie agreed to do so. I was thrilled. So we did that after practice. When we were done and heading back to the dorm, we were flapping our gums about the possibilities.

“My room was fairly close to the door and so we walked down to my room while we were still chatting. We were continuing that conversation and at some point Willie said that he better get back to his room. And I said to him why don’t you room with me or something like that. I told him that my roomy wasn’t coming back. Willie looked at me like he was considering it. He thought about it for a minute and he said, ‘Okay. Let me get my stuff.’ So that was how we became roommates. It was just casual. It wasn’t a big deal. We had a lot in common and it just made a lot of sense.”

Robinson remembered when Kramer and Davis became roommates too.

“it was a monumental moment for the team when Jerry and Willie became roommates,” Robinson said. “They were the first interracial couple so to speak in our team’s history. But you know what, the way they did it, it wasn’t a big issue. It was just two guys rooming together that got along fine.

“We never thought of them as black and white roommates. They were just two guys who get along. They were a great blend. Color never came up. It wasn’t a big issue. It could have been with somebody else, but not with Jerry and Willie.

“In fact on our team, color was never an issue. Coach Lombardi saw something in Willie. Coach wanted Willie to be the liaison between himself and the rest of the club. Primarily the black ballplayers. If anything did come up, regarding any issues for the players, trainers, equipment guys, what have you, we would go to Willie and say that this is wrong.

“After that, Willie would go to Vince and the problem was fixed quickly. And if Vince saw a problem with one of us, he would go to Willie. And Willie would call the player into his room and that matter would be settled quickly as well.”

Kramer concurred with with Robinson said.

“Willie had the respect of the players,” Kramer told me. “Not just the players of color, but all the players.

“When there was a problem when black players were having trouble getting decent housing accommodations at one time, Willie would talk to coach Lombardi about it, and then coach would chew some ass and straighten it out.”

Davis also had a great sense of humor. He told his teammates that his nickname was Dr. Feelgood. Why? Because he made women feel so good.

“Willie was always chatting with the guys,” Kramer said. “He would always get the fellas cracking up with his jokes and humor.”

Kramer retired after the 1968 season and his last game was against the Chicago Bears at Wrigley Field, while Davis retired after the 1969 season and his last game was against the St. Louis Cardinals at Lambeau Field. The common denominator in each one of those games was the performance of quarterback Don Horn.

In Jerry’s last game in 1968, when Horn came into the game for an injured Zeke Bratkowski, Kramer saw Horn and yelled, “What the hell are you in here for? Where’s Zeke?”

But Horn soon had Kramer and the other players on the Green Bay offense at ease, as No. 13 threw for 187 yards, plus had two touchdown passes without throwing a pick, as the Packers won 28-27.

In Davis’ last game in 1969, one in which Davis spoke to the crowd at Lambeau Field, Horn had a masterful performance, as he threw for 410 yards and also threw five touchdown passes, as the Packers beat the Cardinals 45-28.

Late in the game on the sideline, Davis came up to Horn laughing and said, “You stole my thunder!”

Robinson played with the Packers through the 1972 season and then was traded to the Washington Redskins where he spent the last two years of his NFL career playing under head coach George Allen.

It was in Washington when Robinson played with another Hall of Fame defensive end, Deacon Jones.

“I played behind Willie Davis for five years,” Robinson said. “And in Washington, at the end of his career, I played behind Deacon Jones. After playing with Deacon, I said to myself that he could not carry Willie’s jock strap. Now I’m not trying to say Deacon was a lousy football player, he was a great football player, but he was different from Willie.

“Deacon was the type of player who could execute. Willie was the type of player who could improvise and execute. That was a big difference. You sometimes could fool Deacon. Willie on the other hand, could sense what was coming. Both Deacon and Willie were great players, but Willie could improvise. He could analyze, improvise and then execute.”

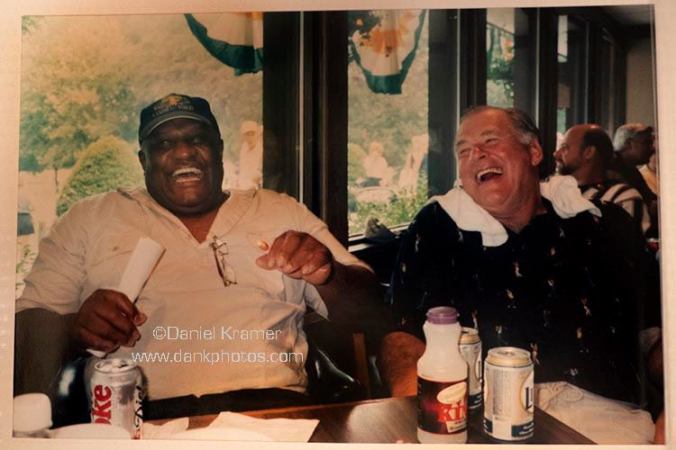

After each of them retired, both Kramer and Davis became very close friends and were often in each other’s company.

“I was always comfortable with Willie,” Kramer said. “It didn’t matter where the hell we were. I could take him anywhere and he could take me anywhere. We were just comfortable with one another.”

One of those times occurred in 1969. But before that happened, Kramer was invited to the inaugural ball for President Richard Nixon, who had just been elected in November of 1968. Jerry was there with some friends, including former NFL player Claude Crabb, attorney John Curtin and Jay Fiondella, the owner of the famous restaurant in Santa Monica, California called Chez Jay.

Jerry’s new book Instant Replay was doing very well and was on the bestseller’s list and was No. 2 at the time. There were some photographers there and a number of people wanted to be photographed with Kramer.

“So I’m trying to be as pleasant as possible and accommodating,” Kramer said. “One of the photos was with an African American lady who was a beauty queen. She was just gorgeous. Plus she was very nice.

“So while this is going on, a photographer from Jet Magazine also took a few photos. Jay, who was standing next to the the photographer from Jet Magazine, decided to add a little spice to the evening. He told the photographer that the black lady I had just taken a picture with was my fiancée. And sure enough, the guy publishes the photos in Jet the next week.

“At the time, I was going through a divorce. So my wife was pissed, my girlfriend was pissed and I was pissed when this came out. I called a lawyer to see what we could do and the guy told me to leave it alone. That the story would go away. I was still pissed, as was the lady in the photo, but the story did go away eventually.

“But about three weeks later, I was going to be speaking at the Milwaukee Athletic Club as the Man of the Year, probably due to the book. There were going to have a dinner for me and the room held around 400 to 500 people. It had a stage and everything. Like a movie theater. So I get there early to check things out like the microphone and the setting in the room. I was there about 15 minutes doing that when Willie comes in.

“So Willie comes in the door which is quite a distance from where I was at. Willie starts laughing. He was laughing so hard he could hardly talk. He is just laughing his ass off. Finally he points at me and me and says, ‘Don’t ever let the white man say I can’t communicate. I room with the guy for a year and he’s ready to cross the road on me!’ Willie had obviously seen the photos in Jet and he was just jerking my chain.”

Yes, since they started rooming together in 1968 moving forward to when Willie passed, Jerry and Willie were very close. How close? Jerry told me that Willie was among his five closest friends in the world.

Another memory that Kramer will never forget was when he and Willie were on a fishing trip in Idaho in the Hell’s Canyon region.

“Yes, we were probably a couple hours from Boise,” Kramer said. “We went up over the mountain there over to a guide’s arrangement there with rooms, boats, fishing equipment and things. We stayed with him a couple of days and did a lot of fishing.

“One day we went about 15 miles upstream. The area was wild ass country because the river was only able to accessed by jetboat. We did a lot of lot of laughing and giggling, as we were doing something that Willie had never done. So we were fishing and Willie catches a carp. Of course they aren’t edible and they are basically a garbage fish.

“So Willie reels it in and the guide looks at it and says, ‘I’ll take care of that son of a bitch!’ He then reaches for his knife which had about an eight or nine inch blade on it and he just slits the fish from stem to stern and throws him in the water. Willie’s eyes became huge and he says, ‘J, what did that man do to that fish? What is that fish guilty of?’

“I know I was surprised, so I know Willie was. So we catch a couple more fish. Then Willie catches another carp and had it almost in the boat, but it’s hanging off his pole. The guide says once again, ‘I’ll take care of that son of a bitch!’ He reaches in a compartment in his boat and he has a 12-gauge there. In one motion he just blows the fish to hell and back with the shotgun. The empty hook and the sinker on Willie’s pole are just hanging there and Willie is just looking down at the water.

“Then Willie looks at the shotgun. Then he looks back at the water where the fish has been vaporized. Then he looks back at the gun. But we just had a great time out there and we came back to the cottage with our fish haul and Willie started cooking them. It was just a great time with a great friend!”

When Jerry would get together with Willie and his wife Carol in California, Jerry always knew he had a great setting during his visit.

“I had the Kramer suite at the Davis home in Marina del Ray,” Kramer said. “It was the big bedroom upstairs looking out at the ocean.”

Besides being teammates, plus being together on various All-Pro teams and Pro Bowl squads, Davis, Kramer and Robinson were all on the Pro Football Hall of Fame All-Decade Team of the 1960s. The three of them were joined on that team by teammates Bart Starr, Paul Hornung, Jim Taylor, Boyd Dowler, Forrest Gregg, Jim Ringo, Ray Nitschke, Herb Adderley, Willie Wood and Don Chandler.

Everyone of those players I just mentioned have busts in Canton. All except for Dowler and Chandler.

Speaking of Canton, Kramer and Robinson were good luck charms to each other when they were each inducted in the Hall of Fame, a place where Davis received a bust in 1981.

“Yes, the night before I was inducted in 2013 in New Orleans, Jerry joined me for dinner and we had a couple of bottles of wine,” Robinson said. “We did the same thing in Minneapolis in 2018 the night before he was inducted.

“The weird part about being in New Orleans, is that was where Jerry didn’t get in as a senior in ’97. I kept thinking, I hope this isn’t déjà vu. I was a bit nervous. But Jerry settled me down. Jerry told me that our dinner would be good luck for me and it was. So when he came up in 2018 in Minneapolis, my son and I went to dinner with Jerry and some people at Ruth’s Chris and had a great steak dinner. Plus we had our wine, too! I was so happy when Jerry got in. Almost as happy when I went in!”

The legacy that Davis, Kramer, Robinson and so many of their Green Bay teammates have created all stems from the guidance of Coach Lombardi. I have talked with many of the players from those championship teams in Green Bay under Lombardi and all have shown exceptional class and humility.

I talk to Kramer more than anyone and it’s a relationship I truly cherish. I first got to meet Robinson at Jerry’s party in Canton before the induction ceremony and when we talked again recently, it was like we were old buddies. I was only able to chat with Willie once and that was when he was on the phone with his wife Carol talking to me, but what an honor that was.

Getting back to Vince Lombardi now. Obviously, he was a great coach and a great teacher. But he was more than that. He was also a great man. A man who molded great football players to be sure, but more importantly than that, he molded great people.

Davis, Kramer and Robinson are a testament to that!